Contributed by Matthew Liotine, PHD

In our last article, we looked at the magnitude of the supply chain risk problem and how it is a major concern for most companies – large or small. Studies have shown that most companies experience one or few supply chain disruptions annually, each resulting in some significant loss. Many of these disruptions involve key suppliers or those below Tier 1. Never the less, many firms still lack commitment to controlling supply chain risk for the reasons of the costs and complexity involved. Consequently, many firms will tend to favor short term ROI solutions versus longer-term solutions that involve investing capital to improve both their supply chain infrastructure and operational resilience. Larger firms will manage risk more strategically using a combination of executive governance and/or data driven approaches. While operational data is increasingly becoming more available, much work is still needed in leveraging such data for strategic risk management. The nature of risk in the supply chain lies with a firm’s exposure to potential disturbances to the supply chain operation. Many of these disturbances can be manifested in various ways, usually in the form of single, multiple or recurring events, conditions or phenomena. In this article, we will examine what kinds of hazards, events or triggers can possibly compromise supply chain weaknesses and can ultimately threaten supply chain operations.

The Changing Nature of Threats

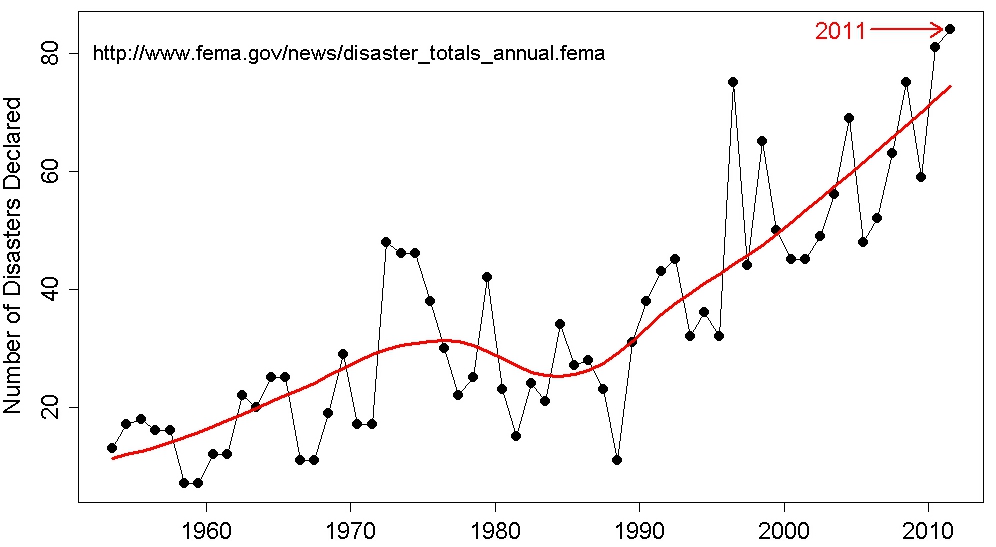

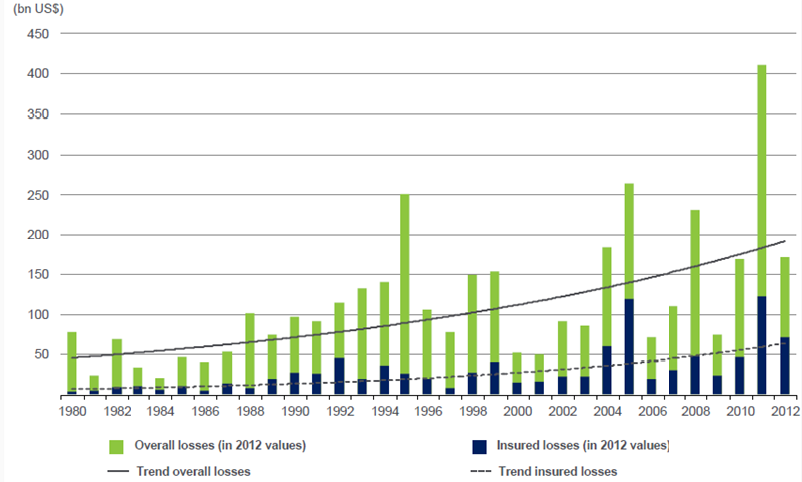

When one thinks about threats to a supply chain, natural disasters usually first come to mind. Figure 1 shows the trend in major U.S. disaster declarations as reported from the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA, 2011). While it is clear that there has been a rising trend in declarations, the reasons may vary from the increase in severe weather events due to climate change, to political influences. Figure 2 shows a trend in worldwide natural catastrophes (Munich RE, 2014).

Figure 1 – Trend in U.S. Disaster Declarations

Figure 2 – Trend in Worldwide Natural Catastrophic Losses

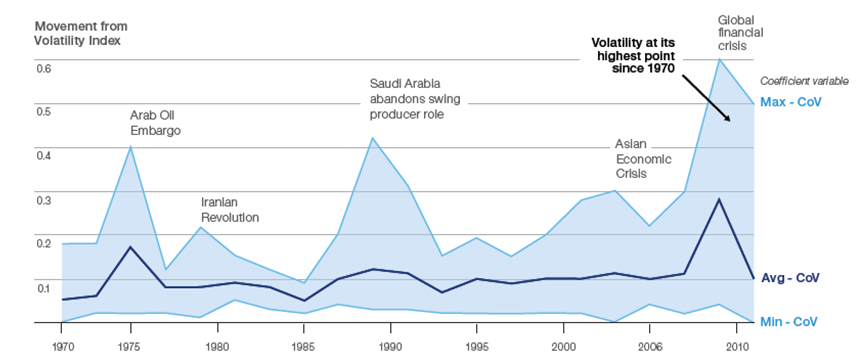

As evident in the Figure, there’s an ever growing trend in measured losses. While natural catastrophes have been occurring since the beginning of time, their effects over the years have been more far reaching due to population growth and insurability trends. These trends, combined with human created disruptions, together have created an environment of increased volatility for supply chains, as depicted in Figure 3 (Martin & Howleg, 2011).

Figure 3 – Trend in Supply Chain Volatility

This Figure shows the annual volatility in a composite set of key business parameters such as exchange rates, interest rates, shipping costs and raw material prices. They are combined into a single volatility index using the coefficient of variation (CoV) of the business indices representing these parameters to produce a normalized volatility metric. While in the far past there has been a timely return to supply chain stability following adverse events, the recent increase in volatility bandwidth questions whether this trend would likely continue. The high collective swings (versus individual swings) in key business parameters, which may be correlated with each other, suggests that an alternative approach to designing supply chains and managing supply chain risk might be preferred.

Volatility can arise from many possible undesirable hazards, conditions or trigger events. The likelihood of such events compromising a supply chain’s vulnerability is regarded as a threat. Table 1 lists categories of possible threat sources and examples within each category. The list was compiled from several studies and is not meant to be all-inclusive (Tummala & Schoenherr, 2011) (World Economic Forum, 2012) (Accenture and World Economic Forum, 2013) (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004).

Table 1 – Supply Chain Threat Sources

Disruptions

Capacity

Information System

Sovereign Regional instability

Strategy & Operations

|

Demand/Customer

Process Design changes

Procurement Unqualified supplier

Transportation Paperwork and scheduling

Structural Fragmentation along the supply chain

|

The Changing Course in Risk Management

Many supply chains are designed under the assumption of operating in stable environment (Martin C. H., 2011). While approaches such as Just-in-Time (JIT) and product-focused production are designed to minimize variation, maximize efficiency and ultimately reduce costs, they require a more rigid command-control management strategy which may not necessarily respond well in a volatile environment. In addition, the effects of volatility can be further amplified in a rigid supply chain that lacks resiliency. Building supply chain resiliency may counter the notion of an efficient operation, since it requires the addition and re-allocation of capacity, inventory and other resources that could serve as shock absorbers to withstand disruption. Since these controls will entail added costs, the use of a risk analysis methodology would be an effective tool in helping firms identify, evaluate and prioritize the most cost-effective risk-control options. It was clearly evident in Table 1 that there can be numerous sources of threats to a supply chain. However, since many threats can have similar outcomes on a supply chain operation, control options can be devised using an “all hazards” philosophy, which entails implementing controls to minimize the common effects of multiple threats or threat categories.

Conclusions

Supply chain disruptions can arise from many sources, both natural and man-made. Current trends indicate a continued rise in measured losses from natural events and increased business volatility in response to man-made events. Traditional supply chain structures designed for operational efficiency may not necessarily be able to withstand disruptions arising from numerous threat sources. Creating a more resilient supply chain may require the use of risk assessment tools and methods to help decision-makers identify the most cost effective controls that could minimize the common effects arising from multiple threats. In the next article, we will examine some common supply chain vulnerabilities and their ensuing risks.

Bibliography

Accenture and World Economic Forum. (2013). Building Resilience in Supply Chains. Accenture.

Chopra, S., & Sodhi, M. S. (2004). Managing Risk To Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(1), 53-61.

FEMA. (2011). Democratic Blog News. Retrieved from http://www.demblognews.com/2011/09/water-development-board-report-says.html

Martin, C. H. (2011). Supply Chain 2.0: Managing Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41(1), 63-82.

Martin, C., & Howleg, M. (2011). Supply Chain 2.0: Managing Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41(1), 63-82.

Munich RE. (2014, January). Topics Geo: After the Floods. Munchen: Munich RE.

Tummala, R., & Schoenherr, T. (2011). Assessing and Managing Rrisks Using the Supply Chain Risk Management Process (SCRMP). Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 16(6), 474–483.

World Economic Forum. (2012). New Models for Addressing Supply Chain and Transport Risk. World Economic Forum.

Leave A Comment